Industrial Chic

Industrial chic, and rugged pendant lighting in particular, has been a part of the interior designer’s palette for longer than many of us might imagine. It now has a role in improving life and work in the office.

Reclaimed, repurposed or replicated, original lamps are, today, a feature of hipster hangouts and banker bars from Antwerp to Zurich and an obvious fit with loft living though oddly rare in the workplace itself. But as far back as the 1920s, the Bauhaus designers Marianne Brandt and Hans Przyrembel recognized the aesthetic value inherent in what others saw as workaday, unremarkable and purely functional. This appreciation grew in part from the ethos of the design school, which aimed to reunite manufacturing and the applied arts.

The multitalented artist, sculptor and designer Brandt joined the school in 1923, where she studied under László Moholy-Nagy in the metal workshop, as did Przyrembel. She rose to become the workshop’s director and designed numerous lamps including the 1924 counter-weighted, industrial ceiling lamp for Körting & Mathiesen, an instant classic that immediately went into mass production.

‘the relationship between the directly lit and the unlit areas of a room, plus lighting of such strength that the reflected light is sufficient to illuminate unlit areas.’ Poul Henningsen

‘the relationship between the directly lit and the unlit areas of a room, plus lighting of such strength that the reflected light is sufficient to illuminate unlit areas.’ Poul Henningsen

The architect Walter Gropius also chose the lamp for his own dining room; its design – encompassing use and ornament – transcended barriers between work and home and in doing so challenged concepts of class, job and what would, far later, become known as work/life balance.

It was not only in Germany between the wars that these notions were being interrogated. Edward Hopper’s 1927 painting Automat examines their down-side: a woman sits alone at a table in a restaurant where the food comes from vending machines; behind her a window reflects lines of ceiling lights redolent of high-bay factory lighting, a metaphor for alienation. In the 1960s movie The Apartment Jack Lemmon’s little man character works in a huge, soulless open-plan office with seemingly infinite ranks of cubicles under an endless grid of lights; the office as assembly line, the worker as anonymous component. It is a backdrop that is still quoted without any sense of irony in standard office fit-outs designed to comply with the letter if not the spirit of regulations and guidelines on workplace lighting.

Their main fault is uniformity and, more often than not, concentrating on the quantity not the quality of the lighting. The result is all too frequently a sterile work environment that imbues mild sensory deprivation and a feeling of loss of control.

In 1924, though, the Danish designer Poul Henningsen said that, ‘the whole trick is not directly illuminating more of a room than is strictly necessary. The pendant form of industrial lighting appealed to Brandt and others because it provides both ambient and task lighting.

Matyas Szaplonczai of Busho Studio Budapest collects vintage industrial lighting.

Credit Busho Studio.

Either side of the Atlantic, a trade is growing in Soviet era factory lighting salvaged from old bus depots, mines and processing plants in Eastern Europe. They were conceived by anonymous ‘artist-constructors’ ordered to concentrate on utility, adaptability and longevity.

Like the even rarer surviving examples of original industrial lighting from the West, they were rugged and utilitarian, free of pointless elaboration. They were also constructed in ‘honest’ materials such as aluminium, Bakelite and copper, which speak of the dignity of labour and the value of the worker of hand or brain.

If the revival and re-use of these designs rests of nostalgia that is no bad thing; a century ago nostalgia was a diagnosis of morbid home-sickness but psychologists have since come to see it as a source of comfort. Industrial-style pendant lighting thus offers to ameliorate or provide an antidote to the blandness of most modern office lighting, one with the potential to satisfy the contemporary needs of office workers in terms of form and function.

TEXT FRANCIS PEARCE

FOTO VARIOUS

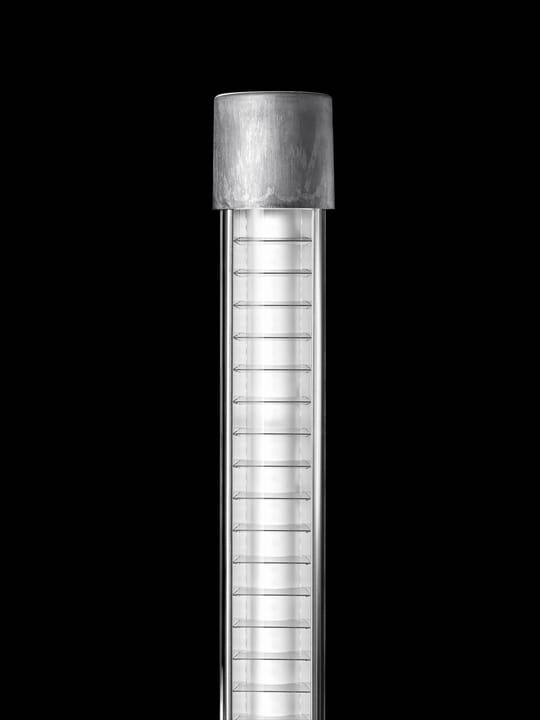

Discover Pondero

A flirt with the shape of the retro fluorescent lamp, but in a modern and urban shape. That is the Pondero; a pendant luminaire in a body of untreated steel with aluminium gables. Already a contemporary classic from Fagerhult.

Läs merRelaterade nyheter

Omvänt mentorskap: ”Allt ledarskap handlar om människor”

Under det senaste halvåret har sexton ledare från bolag i Jönköpings län haft varsin mentor via programmet Omvänt Mentorskap. Det som gör det just »omvänt« är att mentorerna är yngre och i början av sina yrkeskarriärer medan adepterna är mer seniora. Kristoffer Emanuelsson, produktionschef på Fagerhult, och Maria Liljeqvist, enhetschef inom hemtjänst i Jönköpings kommun, är ett av mentorsparen. Hej Maria och Kristoffer! Nu är Omvänt mentorskap över, vad har ni haft fokus på i ert samarbete?Kristoffer: ”Vi har inte haft några specifika mål utan har reflekterat och pratat, och så har Maria kommit med inspel på hur jag kan tänka i min vardag.”Maria: ”Jag tycker vi har haft en tydlig tråd där vi utgått från Kristoffers frågeställningar och reflekterat kring dem.” Kristoffer, var det något särskilt som du ville lyfta – och som du tar med dig? ”Jag ville fokusera på hur jag kan engagera kollegor och vi landade i flera diskussioner kring feedback. Det är lätt att fastna i det klassiska »Bra jobbat!« men det kan behövas lite mer utvecklande kommunikation och det vill jag bli bättre på gentemot mina närmaste medarbetare.” Maria flikar in: ”Jag sa till Kristoffer; du får inte säga »Bra jobbat!« om du inte också utvecklar vad som gjordes bra. Det är så lätt att fastna där.” Omvänt mentorskap 1 Att bryta invanda mönster är kan vara en utmaning, hur har det känts att kliva utanför komfortzonen? Kristoffer: ”Redan vid anmälan så bestämde jag mig för att ge detta en verklig chans. Annars är det ju ingen idé! Jag tycker det är viktigt att poängtera att det till stor del hänger på ens egen inställning. Att man verkligen vill, och vågar vara lite obekväm. Vi har haft bra diskussioner och samtidigt väldigt roligt, och det är ju alltid viktigt.” Maria: ”Jag tycker Kristoffer har varit modig och vågat testa de metoder vi diskuterat. Det har gjort att vi hela tiden kommit vidare.” Maria, har du lärt dig något som du tar med dig – utöver din roll som mentor? Maria: ”Ja, absolut! Det är så tydligt, att även om vi jobbar i väldigt olika miljöer så handlar ledarskapet alltid om människor och individer, och hur vi leder dem. Det är en värdefull insikt. Dessutom har vi haft roligt, och jag har stärkts i min egen roll som ledare genom att ha en senior ledare som lyssnar, tar till sig och provar mina idéer och tankar om ledarskap.” Ni jobbar i vitt skilda branscher, har olika lång ledarerfarenhet och är nya bekantskaper för varandra – vad tar ni med er från det? Maria: ”Vi är ganska olika som personer, och det har varit intressant att reflektera kring det i olika scenarier och hur det påverkar ledarskapet. Vi har lärt oss mycket av varandra.” Kristoffer: ”Jag tycker det är viktigt att vara öppen med sina brister, och samtidigt våga tänka nytt. Och kanske lägga eventuella skillnader kring hur länge man har varit ledare eller ålder åt sidan – och fokusera på att själva samtalet ska bli bra. Maria har ställt en del tuffare frågor där jag känt mig lite obekväm, men det har fått mig att ifrågasätta gamla vanor och varför jag gör saker på ett visst sätt. Det har hon gjort väldigt bra.” Kristoffer, utifrån ditt perspektiv som adept – hur ser du på Omvänt mentorskap? ”Inledningsvis kändes det lite obekvämt, men jag tycker man ska ta chansen att söka. Jag kan verkligen rekommendera det. Att ha en mentor var intressant, och det omvända mentorskapet tycker jag var väldigt givande. Att ta sig tid för reflektion med någon som inte har koppling till min vardag öppnar för andra funderingar och frågor. Vi kommer absolut försöka hålla kontakten.”