Industrial Chic

Industrial chic, and rugged pendant lighting in particular, has been a part of the interior designer’s palette for longer than many of us might imagine. It now has a role in improving life and work in the office.

Reclaimed, repurposed or replicated, original lamps are, today, a feature of hipster hangouts and banker bars from Antwerp to Zurich and an obvious fit with loft living though oddly rare in the workplace itself. But as far back as the 1920s, the Bauhaus designers Marianne Brandt and Hans Przyrembel recognized the aesthetic value inherent in what others saw as workaday, unremarkable and purely functional. This appreciation grew in part from the ethos of the design school, which aimed to reunite manufacturing and the applied arts.

The multitalented artist, sculptor and designer Brandt joined the school in 1923, where she studied under László Moholy-Nagy in the metal workshop, as did Przyrembel. She rose to become the workshop’s director and designed numerous lamps including the 1924 counter-weighted, industrial ceiling lamp for Körting & Mathiesen, an instant classic that immediately went into mass production.

‘the relationship between the directly lit and the unlit areas of a room, plus lighting of such strength that the reflected light is sufficient to illuminate unlit areas.’ Poul Henningsen

‘the relationship between the directly lit and the unlit areas of a room, plus lighting of such strength that the reflected light is sufficient to illuminate unlit areas.’ Poul Henningsen

The architect Walter Gropius also chose the lamp for his own dining room; its design – encompassing use and ornament – transcended barriers between work and home and in doing so challenged concepts of class, job and what would, far later, become known as work/life balance.

It was not only in Germany between the wars that these notions were being interrogated. Edward Hopper’s 1927 painting Automat examines their down-side: a woman sits alone at a table in a restaurant where the food comes from vending machines; behind her a window reflects lines of ceiling lights redolent of high-bay factory lighting, a metaphor for alienation. In the 1960s movie The Apartment Jack Lemmon’s little man character works in a huge, soulless open-plan office with seemingly infinite ranks of cubicles under an endless grid of lights; the office as assembly line, the worker as anonymous component. It is a backdrop that is still quoted without any sense of irony in standard office fit-outs designed to comply with the letter if not the spirit of regulations and guidelines on workplace lighting.

Their main fault is uniformity and, more often than not, concentrating on the quantity not the quality of the lighting. The result is all too frequently a sterile work environment that imbues mild sensory deprivation and a feeling of loss of control.

In 1924, though, the Danish designer Poul Henningsen said that, ‘the whole trick is not directly illuminating more of a room than is strictly necessary. The pendant form of industrial lighting appealed to Brandt and others because it provides both ambient and task lighting.

Matyas Szaplonczai of Busho Studio Budapest collects vintage industrial lighting.

Credit Busho Studio.

Either side of the Atlantic, a trade is growing in Soviet era factory lighting salvaged from old bus depots, mines and processing plants in Eastern Europe. They were conceived by anonymous ‘artist-constructors’ ordered to concentrate on utility, adaptability and longevity.

Like the even rarer surviving examples of original industrial lighting from the West, they were rugged and utilitarian, free of pointless elaboration. They were also constructed in ‘honest’ materials such as aluminium, Bakelite and copper, which speak of the dignity of labour and the value of the worker of hand or brain.

If the revival and re-use of these designs rests of nostalgia that is no bad thing; a century ago nostalgia was a diagnosis of morbid home-sickness but psychologists have since come to see it as a source of comfort. Industrial-style pendant lighting thus offers to ameliorate or provide an antidote to the blandness of most modern office lighting, one with the potential to satisfy the contemporary needs of office workers in terms of form and function.

TEXT FRANCIS PEARCE

PHOTO VARIOUS

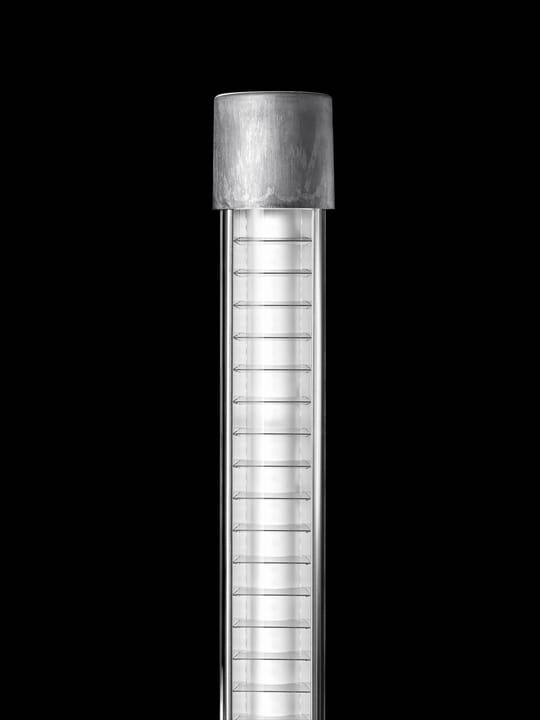

Discover Pondero

A flirt with the shape of the retro fluorescent lamp, but in a modern and urban shape. That is the Pondero; a pendant luminaire in a body of untreated steel with aluminium gables. Already a contemporary classic from Fagerhult.

Read moreRelated News

Melanopic lux: lighting for education influenced by human biology

Light is essential in our daily lives, influencing our ability to see, overall well-being and performance. In educational environments, lighting quality can significantly impact students' focus, mood, and energy levels. So, how do we know what is the right amount and quality of light for this setting? Traditionally, light has been measured in lux, a unit of measurement for the intensity of light. It's used to measure how much light falls on a surface or the amount of light in a given space. One lux is the amount of light that falls on a surface that is one square meter in area when one lumen of light is spread out evenly. Recent advancements in research have unveiled the importance of melanopic lux, which goes beyond mere visibility. This measures how effectively light stimulates specific eye cells that regulate crucial non-visual functions such as sleep and alertness. In classrooms and lecture theatres, the melanopic ratio has become vital in lighting design, enabling educators to create spaces that support visual tasks and align with students' biological rhythms. In this article, we explore how lighting solutions can align with our biology, and how this helps to create optimum conditions for educational environments. The science of vision and light The human eye is a remarkable organ designed for high-resolution colour vision within a small area (approximately 2 degrees of the visual field) while relying on peripheral vision for motion detection. This dual-function system, shaped by evolution for survival, continues to influence how we perceive and interact with our surroundings. Our eyes are particularly susceptible to green and yellow light, reflecting our evolutionary adaptation to naturally lit environments. In contrast, blue light, which is chief in modern LED lighting, requires higher intensity to be perceived at the same level. Effective lighting design carefully considers brightness, timing, and distribution to support visual clarity and biological functions like mood and alertness. For example, exposure to bright light in the morning helps regulate circadian rhythms, boosting alertness and mitigating the effects of seasonal darkness. This is particularly important in educational environments, such as schools and universities, where lighting impacts mood, focus, and overall performance. Our Organic Response system provides an innovative solution tailored for these spaces. This smart lighting technology automatically optimises light levels, featuring daylight-responsive sensors and advanced occupancy detection, maintaining a balance between natural and artificial light. Doing so supports visual comfort and reduces energy consumption, making it an ideal choice for creating dynamic, efficient, and student-friendly learning environments. To further support students, well-lit spaces with minimal glare are essential for reducing eye strain and maintaining focus during extended study sessions. Adjusting light intensity and colour temperature for different tasks—such as reading, group discussions, or creative activities—enhances light's visual and non-visual effects. By integrating thoughtful lighting strategies like those offered by Organic Response, educational environments can promote healthier, more productive, and engaging learning experiences. Integrative lighting: Supporting health and well-being. Integrative lighting (also referred to as human-centred lighting) combines visual and non-visual benefits (such as emotional effects) to support biological rhythms and psychological well-being. This approach goes beyond traditional lighting solutions by considering how light impacts circadian rhythms and hormonal balance. Light exposure in the morning is critical for suppressing melatonin (the sleep hormone) and increasing cortisol (the alertness hormone). Proper timing helps align students' natural rhythms with school schedules, which often require a lot of focus. Consistent exposure to bright, cool light early in the day can enhance energy levels and cognitive performance. The melanopic ratio compares the spectral composition of a light source with daylight. Using this information, you can determine its melanopic lighting intensity. This enables the design of lighting setups that precisely meet both visual and biological lighting needs. Lighting recommendations for educational spaces Each learning environment has unique lighting needs. Libraries benefit from direct lighting on the floor, paired with ambient lighting on walls and ceilings. Vertical shelf lighting (200-300 lx) makes it easier to browse titles. Lecture halls, on the other hand, require glare-free, comfortable lighting with flexible control, ideally with pre-programmed scenarios. In auditoriums and classrooms, strong vertical lighting is crucial for clear visual communication, especially over greater distances, enhancing facial expressions and engagement. General lighting recommendations apply to all educational spaces. Our solutions meet industry standards, ensuring reading and writing areas maintain 500 lx for effective visual tasks. Using daylight-responsive sensors for luminaire rows can reduce energy consumption while maximising natural light. The number and arrangement of luminaires should be adjusted based on the room's size and function to ensure consistent illumination. The role of dynamic lighting A Double Dynamic lighting system can be a game-changer in educational environments. It allows for intensity and colour temperature adjustments to match the specific needs of activities, from quiet reading sessions to collaborative group work. Fagerhult's distinct approach to lighting means that our design is human-centric; we integrate scientific insight into light and human psychology, creating environments that support academic performance and well-being. Our focus on energy efficiency also means our advanced control systems optimise light usage while minimising energy consumption, contributing to a building’s sustainability goals. The customisable setting and flexible solutions ensure that educational environments can create tailored lighting profiles for different times of the day or specific learning activities. Long-term benefits of melanopic lighting Melanopic lighting, designed to mimic the natural light spectrum, helps regulate the circadian rhythm, which is essential for maintaining focus, energy, and emotional balance. In classrooms and study areas, proper lighting can reduce eye strain, improve sleep patterns, and enhance mood, which are critical for students' mental health and academic performance. By incorporating lighting that aligns with our biological needs, schools and universities can foster healthier, more productive learning environments,. This is particularly important during the winter months when daylight is limited. Whether through advanced tuneable white light systems, designs that maximise daylight, or energy-efficient solutions, we are dedicated to leading the way in lighting innovation for educational environments, delivering brighter futures—one classroom at a time.

The inspiration behind Nobel Week Lights: ”Light, art and technology intertwined.”

Nobel Week Lights has quickly become a beloved public celebration. During Nobel Week, Stockholm residents flock outdoors to marvel at the spectacular light installations, where contemporary lighting technology meets artistic expression. ”We aim to create a moment of gathering: around light and around something meaningful”, says Lara Szabo Greisman. Nobel Week Lights is a light festival that illuminates Stockholm during the darkest time of the year – a free cultural experience for everyone. Presented by the Nobel Prize Museum, the festival invites international and local artists, designers and students to create light artworks inspired by the Nobel Prize. The installations shed new light on the scientific discoveries, literature and peace efforts of Nobel laureates while offering a fresh perspective on the city. Fagerhult is Principal Partner of Nobel Week Lights 2024, and this year’s edition features 16 different light installations across Stockholm. The artworks can be experienced from 7–15 December, including ”The Wave”, a light installation by the art collective Vertigo, located in front of the Parliament House where visitors can walk right through the luminous wave. The Wave by Vertigo ”Light and art and creativity is incredibly intertwined because these are technologies that are constantly evolving. So part of the fun working with the artists is that they are constantly testing new technologies. And we see these incredible visual results which are based on just pure innovation”, says Lara Szabo Greisman, co-founder and producer of Nobel Week Lights. Lara Lara Szabo Greisman and Leading Lights by Les Ateliers BK The significance of light as a collective force, its ability to encapsulate life and death, joy and sorrow – indeed, the very essence of what it means to be human – makes lighting a powerful medium of artistic expression, she argues: ”The dream for the festival is that this becomes a personal experience for each and every member of the audience. A moment that they remember and cherish . A moment that they think about later and bring forward as their story of connecting with the city.”